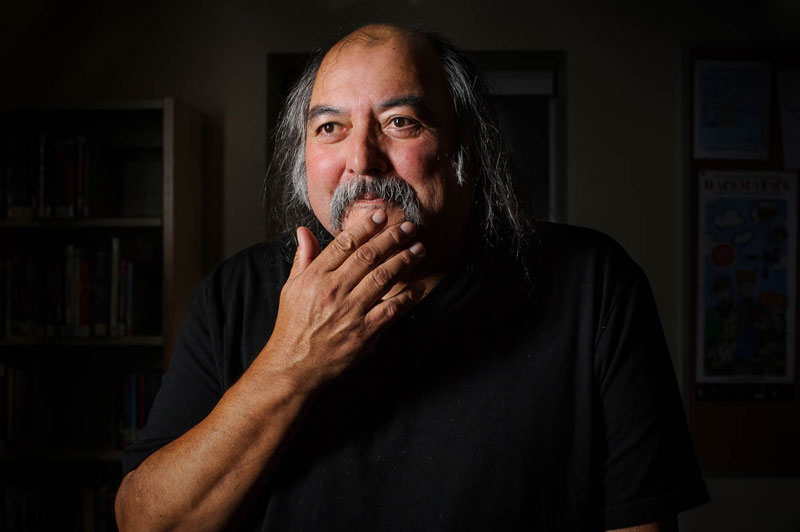

About Alan Syliboy

Biography

Alan Syliboy grew up believing that native art was generic. “As a youth, I found painting difficult and painful, because I was unsure of my identity.” But his confidence grew in 1972 when he studied privately with Shirley Bear. He then attended the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, where 25 years later, he was invited to sit on the Board of Governors. Syliboy looked to the indigenous Mi’kmaq petroglyph tradition for inspiration and developed his own artistic vocabulary out of those forms. His popularization of these symbolic icons has conferred on them a mainstream legitimacy that restores community pride in its Mi’kmaq heritage.

Alan still lives and works in Millbrook, NS, where he was born and raised. He creates his art in his studio in Truro, NS.

Artist Statement

“I see making art as a way of organizing chaos. Sometimes within the chaos of making a painting, a symbol in the shape of a moose or a caribou will walk through my consciousness, in a form that resembles an ancient petroglyph. My work is inspired by the ancient petroglyphs that were carved in stone by my ancestors on walls in caves, as a way to capture and respect the spirit of the subject. When I paint these images, I feel I am channeling a way to bring their spirits back into our consciousness. At one time, these drawings were predominant and lived within our culture. Today, most are no longer visible in their original environments, but I believe the earth has a memory of the spirits they contained. My work lives in the moment but is profoundly influenced by the past; this gives me my bearings as an artist, and as a human being. My ancestors have provided me with a spiritual global navigation system, and I like to believe that what I do helps to keep the spirits evolving.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.